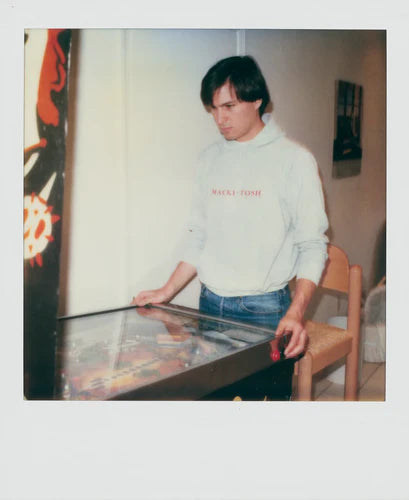

Steve Jobs Speech at the International Design Conference in Aspen

“Computers and society are out on a first date.”Steve spoke to designers at this annual gathering in Aspen, Colorado, on June 15, 1983, five months after Apple introduced the Lisa computer.

How many of you are over thirty-six years old? You were born pre-computer. Computers are thirty-six years old. I think there’s going to be a little slice in the timeline of history as we look back, a pretty meaningful slice right there. A lot of you are products of the television generation. I’m pretty much a product of the television generation, but to some extent starting to be a product of the computer generation.

But the kids growing up now are definitely products of the computer generation, and in their lifetimes the computer will become the predominant medium of communication, just as the television took over from the radio, took over from even the book.

How many of you own an Apple? Any? Or just any personal computer?

Uh-oh.

How many of you have used one, or seen one, or anything like that? Good.

Computers are really dumb. They’re exceptionally simple, but they’re really fast. The raw instructions that we have to feed these little microprocessors—or even these giant Cray-1 supercomputers—are the most trivial of instructions. They get some data from there, get a number from here, add two numbers together, and test to see if it’s bigger than zero. It’s the most mundane thing you could ever imagine.

But here’s the key thing: let’s say I could move a hundred times faster than anyone in here. In the blink of your eye, I could run out there, grab a bouquet of fresh spring flowers, run back in here, and snap my fingers. You would all think I was a magician. And yet I would basically be doing a series of really simple instructions: running out there, grabbing some flowers, running back, snapping my fingers. But I could just do them so fast that you would think that there was something magical going on.

And it’s the exact same way with a computer. It can do about a million instructions per second. And so we tend to think there’s something magical going on, when in reality, it’s just a series of simple instructions.

One of the reasons I’m here is because I need your help. If you’ve looked at computers, they look like garbage. All the great product designers are off designing automobiles or buildings. But hardly any of them are designing computers. If we take a look, we’re going to sell 3 million computers this year, 10 million in ’86, whether they look like a piece of shit or they look great. People are just going to suck this stuff up so fast no matter what it looks like. And it doesn’t cost any more money to make them look great. They are going to be these new objects that are going to be in everyone’s working environment, everyone’s educational environment, and everyone’s home environment. We have a shot [at] putting a great object there—and if we don’t, we’re going to put one more piece-of-junk object there.

By ’86, ’87, pick a year, people are going to spend more time interacting with these machines than they do interacting with automobiles today. People are going to be spending two, three hours a day interacting with these machines—longer than they spend in the car. And so the industrial design, the software design, and how people interact with these things certainly must be given the consideration that we give automobiles today—if not a lot more.

If you take a look, what we’ve got is a situation where most automobiles are not being designed in the United States. Televisions? Audio electronics? Watches, cameras, bicycles, calculators, you name it: most of the objects of our lives are not designed in America. We’ve blown it. We’ve blown it from an industrial point of view because we’ve lost the markets to foreign competitors. We’ve also blown it from a design point of view.

And I think we have a chance with this new computing technology meeting people in the eighties—the fact that computers and society are out on a first date in the eighties. We have a chance to make these things beautiful, and we have a chance to communicate something through the design of the objects themselves.

When I was going to school, I had a few great teachers and a lot of mediocre teachers. And the thing that probably kept me out of jail was the books. I could go and read what Aristotle or Plato wrote without an intermediary in the way. And a book was a phenomenal thing. It got right from the source to the destination without anything in the middle.

The problem was, you can’t ask Aristotle a question. And I think, as we look towards the next fifty to one hundred years, if we really can come up with these machines that can capture an underlying spirit, or an underlying set of principles, or an underlying way of looking at the world, then, when the next Aristotle comes around, maybe if he carries around one of these machines with him his whole life—his or her whole life—and types in all this stuff, then maybe someday, after this person’s dead and gone, we can ask this machine, “Hey, what would Aristotle have said? What about this?” And maybe we won’t get the right answer, but maybe we will. And that’s really exciting to me. And that’s one of the reasons I’m doing what I’m doing.

So, what do you want to talk about?

Steve answered questions at two conference sessions.

How are these computers all going to work together? They’re probably going to work together a lot like people do. Sometimes they’re going to work together really well, and other times they’re not going to work together so well.

What’s happened, there’s been a few installations where people have hooked these things together. The one installation that stands out is at Xerox Palo Alto Research Center, or PARC, for short. And they hooked about a hundred computers together on what’s called a local area network, which is just a cable that carries all this information back and forth. […]

Then an interesting thing happened. There were twenty people interested in volleyball. So a volleyball distribution list evolved, and then, when the volleyball game next week was changed, you’d write a quick memo and send it to the volleyball distribution list. Then there was a Chinese food cooking list. And before long, there were more lists than people.

And it was a very, very interesting phenomenon, because I think that that’s exactly what’s going to happen as we start to tie these things [computers] together: they’re going to facilitate communication and facilitate bringing people together in the special interests that they have.

And we’re about five years away from really solving the problems of hooking these computers together in the office. And we’re about ten to fifteen years away from solving the problems of hooking them together in the home. A lot of people are working on it, but it’s a pretty fierce problem.

Now, Apple’s strategy is really simple. What we want to do is put an incredibly great computer in a book that you carry around with you, that you can learn how to use in twenty minutes. That’s what we want to do. And we want to do it this decade. And we really want to do it with a radio link in it so you don’t have to hook up to anything—you’re in communication with all these larger databases and other computers. We don’t know how to do that now. It’s impossible technically.

We’re trying to get away from programming. We’ve got to get away from programming because people don’t want to program computers. People want to use computers.

We [at Apple] feel that, for some crazy reason, we’re in the right place at the right time to put something back. And what I mean by that is, most of us didn’t make the clothes we’re wearing, and we didn’t cook or grow the food that we eat, and we’re speaking a language that was developed by other people, and we use a mathematics that was developed by other people. We are constantly taking.

And the ability to put something back into the pool of human experience is extremely neat. I think that everyone knows that in the next ten years we have the chance to really do that. And we [will] look back—and while we’re doing it, it’s pretty fun, too—we will look back and say, “God, we were a part of that!”

We started with nothing. So whenever you start with nothing, you can always shoot for the moon. You have nothing to lose. And the thing that happens is—when you sort of get something, it’s very easy to go into cover-your-ass mode, and then you become conservative and vote for Ronnie. So what we’re trying to do is to realize the very amazing time that we’re in and not go into that mode.

I can’t tell you why you need a home computer right now. I mean, people ask me, “Why should I buy a computer in my home?”

And I say, “Well, to learn about it, to run some fun simulations. If you’ve got some kids, they should probably know about it in terms of literacy. They can probably get some good educational software, especially if they’re younger.

“You can hook up to the source and, you know, do whatever you’re going to do. Meet women, I don’t know. But other than that, there’s no good reason to buy one for your house right now. But there will be. There will be.”

I don’t think finance is what drives people at Apple. I don’t think it’s money, but feeling like you own a piece of the company, and this is your damn company, and if you see something … We always tell people, “You work for Apple first and your boss second.” We feel pretty strongly about that.

When you have a million people using something, then that’s when creativity really starts to happen on a very rapid scale. […] We need some revolutions like [the] Lisa [computer], but we also then need to get millions of units out there and let the world innovate—because the world’s pretty good at innovating, we’ve found.

Comments